-40%

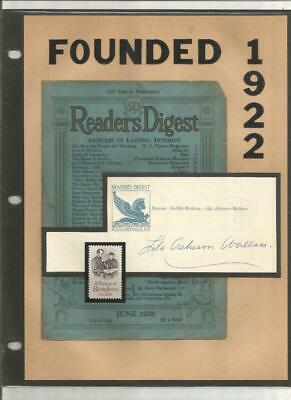

PRESIDENT OF HARVARD,CHARLES W. ELIOT, 1887 BUYING SHIP TICKETS TO GIBRALTAR

$ 21.12

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Handwritten Letter Signed...."....Please find enclosed my cheque for 0.00 being passage-money

for two persons to Gibraltar in room A, on the Independente Jan 26th

from New York Yurs truly Charles W. Eliot"

He would be traveling on the "Independente."

small corner bend lower left....couple light mounting remnants on

reverse at top. o/w f-vf as pictured.

Charles William Eliot

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Charles William Eliot

21st

President of Harvard University

In office

1869–1909

Preceded by

Thomas Hill

Succeeded by

A. Lawrence Lowell

Personal details

Born

March 20, 1834

Boston

,

Massachusetts

Died

August 22, 1926 (aged 92)

Northeast Harbor

,

Maine

Spouse(s)

Ellen Derby Peabody

(1858–1869)

Grace Mellen Hopkinson

(1877–1924)

Children

Charles Eliot

Samuel A. Eliot II

Alma mater

Harvard College

Profession

Professor

,

university president

Signature

Charles William Eliot

(March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an

American

academic

who was selected as

Harvard's

president in 1869.

[1]

A member of the prominent

Eliot family

of Boston, he transformed the provincial college into the pre-eminent American

research university

. Eliot served until 1909, having the longest term as president in the university's history.

Early life

Charles Eliot was a scion of the wealthy

Eliot family

of

Boston

. He was the son of politician

Samuel Atkins Eliot

[1]

and his wife Mary (née Lyman) and was the grandson of banker

Samuel Eliot

. He was one of five siblings and the only boy. Eliot graduated from

Boston Latin School

in 1849 and from

Harvard University

in 1853. He was later made an honorary member of the

Hasty Pudding

.

Although he had high expectations and obvious scientific talents, the first fifteen years of Eliot's career were less than auspicious. He was appointed Tutor in Mathematics at Harvard in the fall of 1854, and studied chemistry with

Josiah P. Cooke

.

[2]

In 1858, he was promoted to Assistant Professor of Mathematics and Chemistry. He taught competently, wrote some technical pieces on chemical impurities in industrial

metals

, and busied himself with schemes for the reform of Harvard's

Lawrence Scientific School

.

But his real goal, appointment to the Rumford Professorship of Chemistry, eluded him. This was a particularly bitter blow because of a change in his family's economic circumstances—the financial failure of his father,

Samuel Atkins Eliot

, in the

Panic of 1857

. Eliot had to face the fact that "he had nothing to look to but his teacher's salary and a legacy left to him by his grandfather Lyman." After a bitter struggle over the Rumford chair, Eliot left Harvard in 1863. His friends assumed that he would "be obliged to cut chemistry and go into business in order to earn a livelihood for his family." But instead, he used his grandfather's

legacy

and a small borrowed sum to spend the next two years studying the educational systems of the Old World in Europe.

Studies of European education

Eliot's approach to investigating European education was unusual. He did not confine his attention to educational institutions, but explored the role of education in every aspect of national life. When Eliot visited

schools

, he took an interest in every aspect of institutional operation, from

curriculum

and methods of instruction through physical arrangements and custodial services. But his particular concern was with the relation between education and economic growth:

I have given special attention to the schools here provided for the education of young men for those arts and trades which require some knowledge of scientific principles and their applications, the schools which turn out master workmen, superintendents, and designers for the numerous French industries which demand taste, skill, and special technical instruction. Such schools we need at home. I can't but think that a thorough knowledge of what France has found useful for the development of her resources, may someday enable me to be of use to my country. At this moment, it is humiliating to read the figures which exhibit the increasing importations of all sorts of manufactured goods into America. Especially will it be the interest of Massachusetts to foster by every mean in her power the manufactures which are her main strength.

[3]

Eliot understood the interdependence of education and enterprise. In a letter to his cousin Arthur T. Lyman, he discussed the value to the German chemical industry of discoveries made in university laboratories. He also recognized that, while European universities depended on government for support, American institutions would have to draw on the resources of the wealthy. He wrote to his cousin:

Every one of the famous universities of Europe was founded by Princes or privileged classes—every

Polytechnic

School, which I have visited in France or Germany, has been supported in the main by Government. Now this is not our way of managing these matters of education, and we have not yet found any equivalent, but republican, method of producing the like results. In our generation I hardly expect to see the institutions founded which have produced such results in Europe, and after they are established they do not begin to tell upon the national industries for ten or twenty years. The Puritans thought they must have trained ministers for the Church and they supported Harvard College—when the American people are convinced that they require more competent chemists, engineers, artists, architects, than they now have, they will somehow establish the institutions to train them. In the meantime, freedom and the American spirit of enterprise will do much for us, as in the past ....

[4]

While Eliot was in Europe, he was again presented with the opportunity to enter the world of active business. The

Merrimack Company

, one of the largest textile mills in the United States, tendered him an invitation to become its superintendent. In spite of the urgings of his friends and the attractiveness of what for the time was the enormous salary of 00 (plus a good house, rent free), Eliot, after giving considerable thought to the offer, turned it down. One of his biographers speculated that he surely realized by this time that he had a strong taste for organizing and administration. This post would have given it scope. He must have felt, even if dimly, that if science interested him, it was not because he was first and last a lover of her laws and generalizations, not only because the clarity and precision of science was congenial, but because science answered the questions of practical men and conferred knowledge and power upon those who would perform the labors of their generation.

During nearly two years in Europe he had found himself as much fascinated by what he could learn concerning the methods by which science could be made to help industry as by what he discovered about the organization of institutions of learning. He was thinking much about what his own young country needed, and his hopes for the United States took account of industry and commerce as well as the field of academic endeavor. To be the chief executive officer of a particular business offered only a limited range of influence; but to stand at the intersection of the realm of production and the realm of knowledge offered considerably more.

Crisis in American colleges

In the 1800s, American colleges, controlled by

clergymen

, continued to embrace

classical curricula

that had little relevance to an industrializing nation. Few offered courses in the sciences, modern languages, history, or political economy — and only a handful had

graduate or professional schools

.

[5]

[6]

As businessmen became increasingly reluctant to send their sons to schools whose curricula offered nothing useful — or to donate money for their support, some educational leaders began exploring ways of making higher education more attractive. Some backed the establishment of specialized schools of science and technology, like Harvard's

Lawrence Scientific School

,

Yale's

Sheffield Scientific School

, and the newly chartered

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

, about to offer its first classes in 1865. Others proposed abandoning the classical curriculum, in favor of more

vocational

offerings.

Harvard was in the middle of this crisis. After three undistinguished short-term clerical presidencies in a ten-year period, the college was slowly fading out. Boston's business leaders, many of them Harvard alumni, were pressing for change — though with no clear idea of the kinds of changes they wanted.

Eliot around the time of his arrival at MIT

On his return to the United States in 1865, Eliot accepted an appointment as Professor of Analytical Chemistry at the newly founded Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In that year, an important revolution occurred in the government of Harvard University. The board of overseers had hitherto consisted of the governor, lieutenant-governor, president of the state senate, speaker of the house, secretary of the board of education, and president and treasurer of the university, together with thirty other persons, and these other persons were elected by joint ballot of the two houses of the state legislature.

An opinion had long been gaining ground that it would be better for the community and the interests of learning, as well as for the university, if the power to elect the overseers were transferred from the legislature to the graduates of the college. This change was made in 1865, and at the same time the governor and other state officers ceased to form part of the board. The effect of this change was to greatly strengthen the interest of the alumni in the management of the university, and thus to prepare the way for extensive and thorough reforms. Shortly afterward Dr.

Thomas Hill

resigned the presidency, and after a considerable

interregnum

Eliot succeeded to that office in 1869.

[2]

Harvard presidency

Early in 1869, Eliot had presented his ideas about reforming American higher education in a compelling two-part article, "The New Education," in

The Atlantic Monthly

, the nation's leading journal of opinion. "We are fighting a wilderness, physical and moral," Eliot declared in setting forth his vision of the American university, "for this fight we must be trained and armed."

[7]

The articles resonated powerfully with the businessmen who controlled the Harvard Corporation. Shortly after their appearance, merely 35 years old, he was elected as the youngest president in the history of the nation's oldest university.

With

Booker Washington

and other dignitaries

Eliot's educational vision incorporated important elements of Unitarian and

Emersonian

ideas about character development, framed by a pragmatic understanding of the role of higher education in economic and political leadership. His concern in "The New Education" was not merely curriculum, but the ultimate utility of education. A college education could enable a student to make intelligent choices, but should not attempt to provide specialized vocational or technical training.

Although his methods were pragmatic, Eliot's ultimate goal, like those of the secularized Puritanism of the Boston elite, was a spiritual one. The spiritual desideratum was not otherworldly. It was embedded in the material world and consisted of measurable progress of the human spirit towards mastery of human intelligence over nature — the "moral and spiritual wilderness." While this mastery depended on each individual fully realizing his capacities, it was ultimately a collective achievement and the product of institutions which established the conditions both for individual and collective achievement. Like the Union victory in the

Civil War

, triumph over the moral and physical wilderness and the establishment of mastery required a joining of industrial and cultural forces.

While he proposed the reform of professional schools, the development of research faculties, and, in general, a huge broadening of the curriculum, his blueprint for undergraduate education in crucial ways preserved — and even enhanced — its traditional spiritual and character education functions. Echoing Emerson, he believed that every individual mind had "its own peculiar constitution." The problem, both in terms of fully developing an individual's capacities and in maximizing his social utility, was to present him with a course of study sufficiently representative so as "to reveal to him, or at least to his teachers and parents, his capacities and tastes." An informed choice once made, the individual might pursue whatever specialized branch of knowledge he found congenial.

[5]

But Eliot's goal went well beyond Emersonian self-actualization for its own sake. Framed by the higher purposes of a research university in the service of the nation, specialized expertise could be harnessed to public purposes. "When the revelation of his own peculiar taste and capacity comes to a young man, let him reverently give it welcome, thank God, and take courage," Eliot declared in his inaugural address. He further stated:

Thereafter he knows his way to happy, enthusiastic work, and, God willing, to usefulness and success. The civilization of a people may be inferred from the variety of its tools. There are thousands of years between the stone hatchet and the machine-shop. As tools multiply, each is more ingeniously adapted to its own exclusive purpose. So with the men that make the State. For the individual, concentration, and the highest development of his own peculiar faculty, is the only prudence. But for the State, it is variety, not uniformity, of intellectual product, which is needful.

[8]

On the subject of educational reform, he declared:

As a people, we do not apply to mental activities the principle of division of labor; and we have but a halting faith in special training for high professional employments. The vulgar conceit that a Yankee can turn his hand to anything we insensibly carry into high places, where it is preposterous and criminal. We are accustomed to seeing men leap from farm or shop to court-room or pulpit, and we half believe that common men can safely use the seven-league boots of genius. What amount of knowledge and experience do we habitually demand of our lawgivers? What special training do we ordinarily think necessary for our diplomatists? — although in great emergencies the nation has known where to turn. Only after years of the bitterest experience did we come to believe the professional training of a soldier to be of value in war. This lack of faith in the prophecy of a natural bent, and in the value of a discipline concentrated upon a single object, amounts to a national danger.

[9]

Under Eliot's leadership, Harvard adopted an "elective system" which vastly expanded the range of courses offered and permitted undergraduates unrestricted choice in selecting their courses of study — with a view to enabling them to discover their "natural bents" and pursue them into specialized studies. A monumental expansion of Harvard's graduate and professional school and departments facilitated specialization, while at the same time making the university a center for advanced scientific and technological research. Accompanying this was a shift in pedagogy from recitations and lectures towards classes that put students' achievements to the test and, through a revised grading system, rigorously assessed individual performance.

Eliot's reforms did not go without major criticism. His own kinsman

Samuel Eliot Morison

in his tercentenary history of Harvard made this devastating assessment:

It was due to Eliot’s insistent pressure that the Harvard faculty abolished the Greek requirement for entrance in 1887, after dropping required Latin and Greek for freshman year. His and Harvard’s reputation, the pressure of teachers trained in the new learning, and of parents wanting ‘practical’ instruction for their sons, soon had the classics on the run, in schools as well as colleges; and no equivalent to the classics, for mental training, cultural background, or solid satisfaction in after life, has yet been discovered. It is a hard saying, but Mr. Eliot, more than any other man, is responsible for the greatest educational crime of the century against American youth—depriving him of his classical heritage.

[10]

Opposition to football and other sports

During his tenure, Eliot opposed

football

and tried unsuccessfully to abolish the game at Harvard. In 1905,

The New York Times

reported that he called it "a fight whose strategy and ethics are those of war", that violation of rules cannot be prevented, that "the weaker man is considered the legitimate prey of the stronger" and that "no sport is wholesome in which ungenerous or mean acts which easily escape detection contribute to victory."

[11]

He also made public objections to

baseball

,

basketball

, and

hockey

. He was quoted as saying that

rowing

and

tennis

were the only clean sports.

[12]

Eliot once said:

[T]his year I'm told the team did well because one pitcher had a fine curve ball. I understand that a curve ball is thrown with a deliberate attempt to deceive. Surely this is not an ability we should want to foster at Harvard.

[13]

Attempted acquisition of MIT

During his lengthy tenure as Harvard's leader, Eliot initiated repeated attempts to acquire his former employer, the fledgling

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

, and these efforts continued even after he stepped down from the presidency.

[14]

[15]

The much younger college had considerable financial problems during its first five decades, and had been repeatedly rescued from insolvency by various benefactors, including

George Eastman

, the founder of

Eastman Kodak Company

. The faculty, students, and alumni of MIT often vehemently opposed merger of their school under the Harvard umbrella.

[16]

In 1916, MIT succeeded in moving across the

Charles River

from crowded

Back Bay, Boston

to larger facilities on the southern riverfront of Cambridge, but still faced the prospect of merger with Harvard,

[17]

which was to begin "when the Institute will occupy its splendid new buildings in Cambridge."

[18]

However, in 1917, the

Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

rendered a decision that effectively cancelled plans for a merger,

[15]

and MIT eventually attained independent financial stability. During his life, Eliot had been involved in at least five unsuccessful attempts to absorb MIT into Harvard.

[19]

Personal life

[

edit

]

On October 27, 1858, Eliot married Ellen Derby Peabody of Salem Massachusetts (1836–1869) in Boston at

Kings Chapel

. Ellen was the daughter of

Ephraim Peabody

(1807-1856) and Mary Jane Derby (1807-1892), great-great-granddaughter of

Elias Hasket Derby

(1739-1799). They had four sons, one of whom,

Charles Eliot

(November 1, 1859 – March 25, 1897) became an important

landscape architect

, responsible for Boston's public park system. Another son,

Samuel Atkins Eliot II

(August 24, 1862 – October 15, 1950) became a

Unitarian

minister who was the longest-serving president of the

American Unitarian Association

(1900–1927) and was the first president granted executive authority of that organization.

The

Nobel Prize

-winning poet

T.S. Eliot

was a cousin and attended Harvard from 1906 through 1909, completing his elective undergraduate courses in three instead of the normal four years, which were the last three years of Charles' presidency.

[20]

After Ellen Derby Peabody died at the age of 33 of

tuberculosis

, Eliot married a second wife in 1877, Grace Mellen Hopkinson (1846–1924). This second marriage did not produce any children. Grace was a close relative of Frances Stone Hopkinson, wife of Samuel Atkins Eliot II, Charles's son.

Eliot retired in 1909, having served 40 years as president, the longest term in the university's history, and was honored as Harvard's first president emeritus. He lived another 17 years, dying in

Northeast Harbor, Maine

, in 1926, and was interred in

Mount Auburn Cemetery

in

Cambridge, Massachusetts

.

Legacy

Under Eliot, Harvard became a worldwide university, accepting its students around America using standardized

entrance examinations

and hiring well-known scholars from home and abroad. Eliot was an administrative reformer, reorganizing the

university

's

faculty

into schools and departments and replacing recitations with

lectures

and

seminars

. During his forty-year presidency, the university vastly expanded its facilities, with laboratories, libraries, classrooms, and athletic facilities replacing simple colonial structures. Eliot attracted the support of major donors from among the nation's growing

plutocracy

, making it the wealthiest private university in the world.

Eliot's leadership made Harvard not only the pace-setter for other American schools, but a major figure in the reform of

secondary school

education. Both the elite

boarding schools

, most of them founded during his presidency, and the public

high schools

shaped their

curricula

to meet Harvard's demanding standards. Eliot was a key figure in the creation of standardized admissions examinations, as a founding member of the

College Entrance Examination Board

.

As leader of the nation's wealthiest and best-known university, Eliot was necessarily a celebrated figure whose opinions were sought on a wide variety of matters, from

tax

policy (he offered the first coherent rationale for the charitable

tax exemption

) to the intellectual welfare of the general public.

President Eliot edited the

Harvard Classics

, which together are colloquially known as his Five Foot Shelf

[21]

and which were intended at the time to suggest a foundation for informed discourse, "A good substitute for a liberal education in youth to anyone who would read them with devotion, even if he could spare but fifteen minutes a day for reading."

[22]

Eliot was an articulate opponent of

American imperialism

, and he was opposed to the education of women. Many talented

African Americans

were educated at Harvard during Eliot's tenure, including such notables as

W. E. B. Du Bois

(Class of 1890).

Booker T. Washington

was awarded an honorary degree by Harvard in 1896. Unlike his successor,

A. Lawrence Lowell

, Eliot opposed efforts to limit the admission of

Jews

and

Roman Catholics

.

[23]

[24]

At the same time, Eliot was radically opposed to labor unions, fostering a campus climate where many Harvard students served as strikebreakers; he was called by some "the greatest labor union hater in the country."

[25]

Charles Eliot was a fearless crusader not only for

educational reform

, but for many of the goals of the

progressive movement

—whose most prominent figurehead was

Theodore Roosevelt

(Class of 1880) and most eloquent spokesman was

Herbert Croly

(Class of 1889).

Eliot was also involved in philanthropy. In 1908 he joined the

General Education Board

, in 1913 served on the

International Health Board

, and served as a trustee of the

Rockefeller Foundation

from 1914 to 1917. Helped found the Institute for Government Research (

Brookings Institution

) and serving as trustee. Acted as trustee of the

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

from its beginning in 1910 until 1919. Was an incorporator of the

Boston Museum of Fine Arts

in 1870, and a trustee. Between 1908 and 1925 he served as the chairman of the Museum's Special Advisory Committee on Education. Served as vice president for the National Committee for Mental Hygiene from 1913 till his death.

[26]

Accepted election to be the first president of the

American Social Hygiene Association

. In 1902 became vice president of the

National Civil Service Reform League

, and in 1908 president of the league.

[27]

In celebration of President Eliot's 90 birthday, congratulations came in across the world and notably from two American Presidents. Woodrow Wilson said of him, “No man has ever made a deeper impression of the educational system of a country than President Eliot has upon the educational system of America,” while Theodore Roosevelt exclaimed, “He is the only man in the world I envy.”

[28]

Upon his death in 1926,

The New York Times

published a full-page interview that Eliot had given as he neared the end of his life,

[29]

including excerpts from his writings on education, religion, democracy, labor, "woman", and Americanism.

[3